The French and Indian War

From the Land of Flint to the Land Where the Partridge Drums The Migration from the Mohawk Valley to Kahnawake and Akwesasne

by Darren Bonaparte

Source: Seven Generations, by David Blanchard, published by the Kahnawake Survival School

Last week we saw how religious, political, and economic interference split the Mohawk Nation in half, resulting in the creation of a new Mohawk community of Kahnawake near Montreal. By 1755, this community had grown so large that another settlement was established in the Land Where The Partridge Drums, or Akwesasne. This week’s installment takes a closer look at the period in which this occurred and attempts to settle an old argument…

At present, there is little documentation available about the earliest days of the Akwesasne community. Academics like Jack Frisch and George L. Frear have pinpointed the date of the arrival of the Kahnawake Mohawks only after an exercise in detective work: the dates in most historical accounts vary from 1752 to 1762. The year they actually did arrive, 1755, sets it against a backdrop of rising tensions in Mohawk country that help to explain just why these families left Kahnawake.

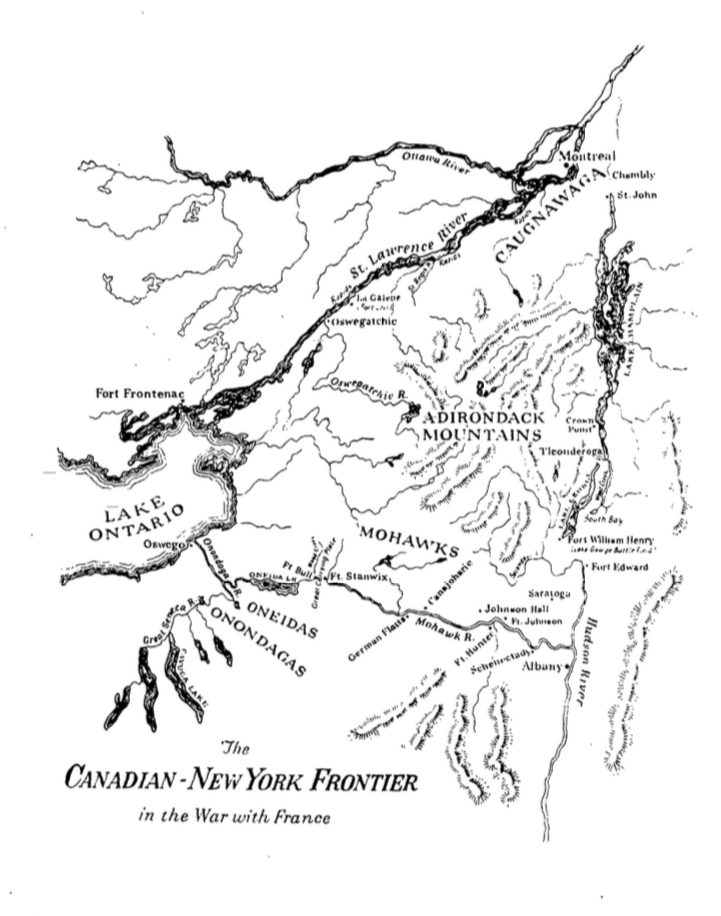

Like Kahnawake, Akwesasne was located on the southern shore of the St. Lawrence River, the powerful waterway that had always been a natural boundary marker between the territories of the Haudenosaunee and their Huron and Algonquin neighbors. As such, the Mohawks considered Akwesasne part of the northern frontier of Mohawk territory.

The French, naturally, saw it from another perspective. As a French Indian Mission, St. Regis was considered a part of the French frontier in its earliest years; it appeared as such on a 1758 map drawn by a French captain named Pouchot. (DRCHSNY 10) The Great War for Empire, also known as the French and Indian War, began right around the time of the Kahnawake migration, and warriors from Kahnawake and other French-allied native groups played a critical role in the defeat of British forces under General Braddock in Ohio during the early days of the conflict. (Flexner 1979:131-133)

Almost immediately after the Kahnawake Mohawks arrived in Akwesasne in 1755, their former neighbors accepted the war belt and accompanied the French army under Baron Dieskau in their advance on the British at Albany. Although the Haudenosaunee Confederacy had so far maintained a policy of neutrality, Britain’s superintendent of Indian Affairs, William Johnson, managed to convince his Mohawk friend, Chief Tiyanoga (also known as Hendrick) to raise a force of about 200 warriors to accompany his forces into battle against the French. (Flexner 1979:143) Tiyanoga was an influential chief. He had been one of three Mohawk “kings” who, with a Mohican companion, traveled to England during Queen Anne’s War for an audience with Her Royal Highness. Throughout his life he led many war parties against the French, sometimes coming into deadly confrontations with Kahnawake Mohawks who knew him as the dreaded “Whitehair.”

One of the young men who accompanied William Johnson and Tiyanoga on this mission was fifteen-year-old Thayendenagea (“Two Sticks Tied Together”), the grandson of one of the other Mohawk “kings” and the brother of Johnson’s Mohawk wife, Molly. Most people know this young warrior by the English name Joseph Brant. This was Joseph’s first taste of combat, but it was not to be his last. The same could not be said for poor Tiyanoga, who would pay dearly for holding too tightly to the Covenant Chain with the English.

When the two armies and their native allies clashed at the Battle of Lake George, the Mohawks were reluctant to fight their own people and even tried to talk each other out of fighting before the first shot was fired. One account of the battle says they initially avoided each other in hand-to-hand combat, even to the point of endangering their European allies. Sadly, there were significant exceptions: the elderly Tiyanoga tried to slip away from the action and stumbled upon a camp of the “French Indians” who promptly killed him. (Flex net 1979:145-146) This battle was an important victory for the British and earned William Johnson the title of Baronet, but it left the southern Mohawks without one of their principal chiefs and deepened the resentment between the two groups of Mohawk people.

By Darren Bonaparte, historian and author of The Wampum Chronicles. Reprinted with permission.

Darren Bonaparte is a cultural historian from the Akwesasne First Nation. He is a frequent lecturer at schools, universities, museums, and historical sites in the United States and Canada. He has written four books, several articles, and the libretto for the McGill Chamber Orchestra’s Aboriginal Visions and Voices. Darren is a former chief of the Mohawk Council of Akwesasne. He is the creator of The Wampum Chronicles and historical advisor to film and television. He currently serves as the Director of the Tribal Historic Preservation Office of the Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe.

Next week:Mohawk vs. Mohawk: The Battle of Lake George