1882: The Year of Pestilence, Death and Solutions in Little Falls

The summer of 1882 was a bad time to be an inhabitant of Little Falls as sickness and death raged throughout the village. In those few months, an estimated sixty people died, with hundreds more sickened – over half of the deaths were of infants and adolescents. Cholera, typhoid fever and “brain congestion”, at the time often lumped together as “malarial disease”, were the culprits. Victims of cholera suffered severe cases of diarrhea and subsequent dehydration, with death sometimes occurring within hours or a few days from the onset of symptoms. Typhoid and “brain congestion” resulted in extremely high fever leading in many cases to shock and death. All three diseases are caused by repulsive fecal-oral transmission. The diseases and their cause were well-known and had been portended a dozen years earlier. The village trustees had been forewarned of their coming, yet nothing had been done. In 1870, the editor of The Herkimer County Journal, Jean Stebbins, referring to the lack of sanitation and clean water in Little Falls, wrote;

“Unless something is done a day of reckoning will come sooner or later. It only needs a hot, dry summer to breed some malarial disease, which cannot fail to carry off hundreds of our citizens. Almost everybody knows it, but no one seems to be willing to make a move towards doing something to rid this village of this terrible breeder of disease.”

The summer of 1882 was hot and dry.

A bit about Little Falls. In 1882 the village had a population of about 7,000, with most of the well to do living in close proximity to Main Street and the middle and lower socio-economic groups residing either near the river or away from the village center. As expected, the majority of businesses and stores were clustered on or near Main Street, and most factories and mills were established near the river to make use of the Mohawk’s waterpower.

None of the streets were paved. During the spring thaw and after heavy rain these thoroughfares would be churned to mud, to which was added the droppings of horses and live stock being driven though the village. Fortunately, planks were often laid at crosswalks. It was also not an uncommon occurrence to encounter dead horses in the street. The village paid individuals fifty cents to remove the dead animals and an additional fifty cents to bury them in the “horse burial ground” at the eastern end of Hancock Street. But most fellows chose to forego the extra half dollar and simply threw the bodies in the river.

In 1882 there was no garbage pick-up in Little Falls. Residents repurposed what they could, the remainder being either buried or burned. For the larger items a dump of sorts was sited on the riverbank near where today’s sewage disposal plant is located.

Little Falls had two slaughterhouses. By village law these slaughterhouses had to be situated away from the village center and could only operate from November 1st to April 1st. Located down by the river, the abattoirs had a convenient place to dispose of the unwanted parts of the animal carcasses – into the river’s current they went. In response to frequent complaints regarding the smells emanating from the slaughterhouses, members of the Little Falls Board of Health were frequent visitors.

Residents of Little Falls received their water in three ways. About half of the people were served by wooden water lines piped in either from springs on Monroe Street (Aqueduct Association) or from springs on the eastern end of Loomis Street (Boyer System). These lines, operated by private entities, delivered water to subscribers via “standpipes” (similar to hydrants) principally along Monroe, Ann, Church, Albany, Loomis and Burwell Streets. In other parts of the village water was obtained from shallow dug wells or from one of the innumerable hillside springs, which at times conveniently flowed into the cellars of homes.

The means of disposing of human waste was archaic at best. Residents along the two major streams that flowed through the village, Furnace Creek and Cemetery Creek (aka Arnold’s Creek), used these waterways as their “sewers.” Homes along the creeks either sent their waste, via pipes, directly into the streams or simply positioned their “necessaries” above them. Furnace Creek ran directly into the Mohawk River, while Cemetery Creek flowed down Monroe and Ann Streets depositing its contents into the old basin (Clinton Park). During dry weather the creek flows were reduced to a trickle and the human waste offensively lingered in these “gutters.”

For those homes not situated near a creek, privies and cesspools served the purpose of collecting human waste. Due to the lack of space, these were often located in close proximity to wells and spring sources. The village of Little Falls sits on bedrock (Gneiss), which is impervious to water. On top of this bedrock is a thin layer of sandstone or limestone, topped off by soil. The contents of the privies and cesspools therefore can only seep down so far and tend, especially in dry weather, to flow laterally into the wells and springs. Civil Engineer E.T. Lansing gave a vivid description of the “sewage” problem in Little Falls writing:

“House drains were permitted to enter their filth into the street gutters and into Furnace and Cemetery creeks. Thus, during the summer months, when water was most needed in the form of rainfall to cleanse the gutters and flush out the creeks, which diminished to mere threads of streams at such periods, and made from their conformation natural precipitating basins for filth, there was no water. Well-water in the lower elevation, upon chemical analysis showed the presence of organic matter in poisonous proportions, and finally the old canal basin, which had been abandoned by the State, still continued to receive the sewage from sewers, as well as liberal contributions of animal and vegetable matter, the nature of which it is needless to detail, but, in the words of Shakespeare, ‘It smelt to high heaven.’

The “day of reckoning”, as editor Jean Stebbins had predicted twelve years earlier, came in the dry summer of 1882.

By early July, 1882 the doctors of Little Falls reported a twenty percent uptick in sickness and death from water-borne diseases. A few weeks later a large number of employees at the Little Falls Knitting Company and at the Eagle Mills were absent from their jobs due to “septic” illness. Each of the factories was inspected by the State Board of Health, which reported that the mills were in a sanitary condition and that the cause of the sickness lay elsewhere. In just a three week period from late August to early September there were seventeen deaths in the village attributed to cholera and “fevers.” Doctors Southworth, Glidden, Garlock, Brainard and Sharer began to plot the location of the cases and determined that those areas of the village down slope from Monroe Street, that were served by wells or springs, had by far the majority of cholera and fever victims. Individuals living on John Street, Furnace Street, Western Avenue (West Main Street today) and on Eastern Avenue (East Main Street today) were at the greatest risk. Each of the doctors was convinced that the cause of the sickness was due to water poisoned by human excrement from privies or cesspools. Water sampled from a well on Western Avenue and sent to Utica for testing revealed that “vegetative material” was present. (Although a few of the doctors still believed that noxious odors emanating from the open sewers, old canal and near stagnant basin was a contributing factor.)

In the pages of the Herkimer County Journal the doctors strongly advised people using well or spring water in the affected areas to immediately stop using wells and springs or, if it was their only source, to boil it. They strongly cautioned people that even if the water looked, smelled and tasted good it could very well contain septic poison, and that it was a fallacy that all spring water was healthy. For a long term solution they recommended that the village eliminate the open gutters, fill in the old canal and construct a closed sewer system.

The Little Falls Board of Trustees heeded the doctor’s advice.

Frank J. Baxter, an engineer from Utica, was engaged in July, and by the end of August Baxter presented a plan, map and estimates for a system of sewerage to be built in the village’s central portion. The plan was unanimously approved by the board. A description of Baxter’s design was offered in The Herkimer County Journal:

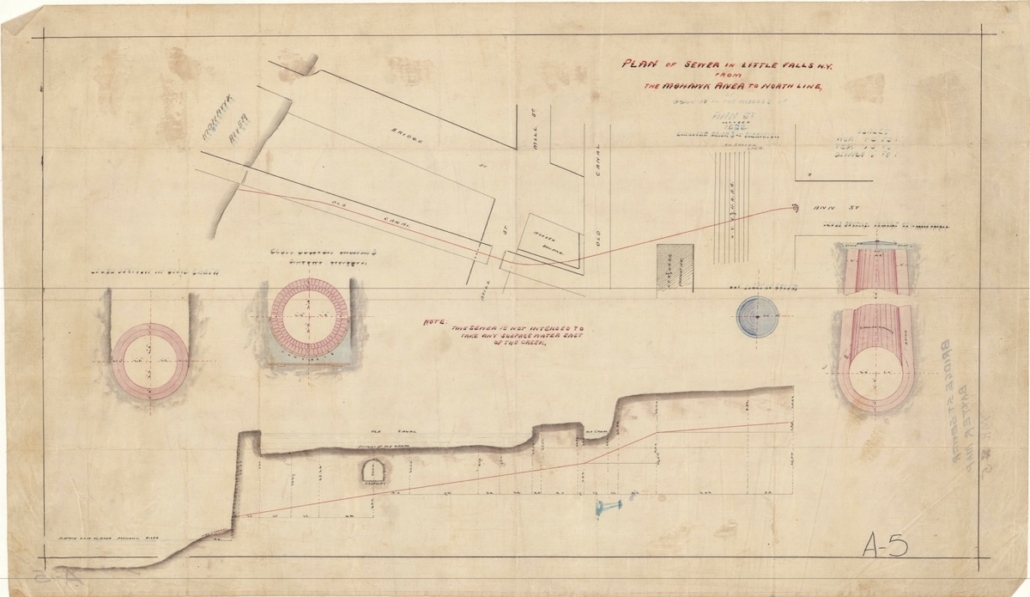

“Mr. Baxter advised the building of a stone arched sewer through Ann Street, of about four feet in diameter from the river to Church Street, and somewhat smaller from Church Street to Monroe Street: the bottom of the sewer to be about ten feet below the surface of the ground, so that all cellars may be drained into it: the course of the sewer from the foot of Ann Street to be through the basin and aqueduct to the river.”

Original 1883 sewer map

The estimated cost of this section of sewer was $17,000 (about $500,000 in 2022) and was to be paid for by the owners directly affected by it and by a general tax. The sewer was to use the flow of Cemetery Creek for flushing, and as an added benefit the sewer would provide for surface drainage from the streets, hopefully alleviating some of the mud.

Construction of this main, or trunk sewer was awarded to S. Sherman, with Watts T. Loomis appointed as the supervising engineer. Work began in early March, 1883 and was completed in June. Although imperfect by today’s standards, lateral sewer lines connected house drains on Church, Monroe and Ann Streets to the main sewer line, which conveyed waste water down Ann Street. At the bottom of Ann Street it passed under the railroad tracks, into the old basin, and then to the aqueduct where it dropped into the river. Within a year of the sewers completion cholera and typhoid cases dropped dramatically. (In June, 2013 heavy rains caused Cemetery Creek to flood. Large sinkholes formed in Ed’s Pizza and in the Kinney Plaza parking lot. It is thought that these sinkholes were caused by the collapse of portions of the 1883 sewer.)

Over the next few years additional trunk lines and laterals would be laid so that the great majority of the village was served by proper sewers (sewers on the south side of Little Falls, and a few peripheral streets would be installed over time.) When the project was completed over eight miles of pipe had been woven under the village’s surface, at a cost of $60,000 (about $1.8 million in 2022). In 1968 the city of Little Falls began construction of a wastewater treatment plant finally eliminating the dumping of raw sewage into the Mohawk River.

In 1886 work began on a 16 mile long system that brought potable water from Salisbury to the households of Little Falls, and water borne disease was virtually eliminated from the village. Over time the streets were paved, the old canal and basin were drained and filled in, the slaughterhouses were closed and Furnace and Cemetery creeks were routed underground.

Today we take these improvements for granted. Imagine what our quality of life would be without them. Think of living with open sewers, filled with human waste, running though our city, or living with the thought that your next drink of water could have mortal consequences. Would we tolerate the noxious odors and general filth all around us? Our predecessors from 1882 couldn’t either, so they did something about it and we benefit today from their actions.

David Krutz is a member of the Little Falls Historical Society.