The Underground Railroad In And Around Little Falls

By Cynthia Holick Foley, Little Falls Historical Society

The Underground Railroad (URR) was a loosely organized network of people, (men and women, African American and white,) dedicated to helping people escape from bondage in the slave–holding states of the South to freedom in the antislavery states of the North and ultimately to Canada in the period before the Civil War. Some slaves fled their owners and followed the “Drinking Gourd,” the Big Dipper (Ursa Major), using its stars to point to the North Star (Polaris), in the Little Dipper (Ursa Minor). At times, the song “Follow the Drinking Gourd” was sung in slave quarters to herald an escape attempt. One slave, Henry “Box” Brown, mailed himself to freedom contorted into a crate on a train for 27 hours.

However, thousands of slaves were guided to freedom via the URR. Those involved in this dangerous enterprise were activists fighting for basic rights of freedom and equality for all. The stations on the railroad were a series of safe houses or terminals where slaves were led by various conductors. Safe houses were often marked by such clues as quilts, often with the flying geese pattern, (geese flying north) hung on lines in their yards or were known to the conductor by word of mouth or other communication. New York was one of the last stops on the URR and became especially important after the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.

In this draconian revision of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, slaves were no longer safe north of the Mason-Dixon Line. Now, they had to flee to Canada to escape capture by both local and federal authorities and subsequent return to their owners. In addition, the law included a $1000 fine and six months imprisonment for any citizen “aiding and abetting a fugitive slave.”

Given the legal consequences, many accounts of safe houses are anecdotal stories shared by family members often in oral histories and occasionally in private letters. However, some black conductors like the Reverend Jermain Wesley Loguen of Syracuse, Gerrit Smith of Peterboro, Harriet Tubman of Auburn, and Frederick Douglass of Rochester were more outspoken both verbally and in writing. All these abolitionists had connections with both Enoch Moore of Little Falls and Zenas Brockett of Brocketts Bridge (Dolgeville).

Loguen, himself a fugitive slave, eventually settled in Syracuse where his house was a known depot on the URR constructed with special accommodations in the basement for hiding fugitive slaves. Often referred to as “the King of the Underground Railroad,” he visited Little Falls in 1844 and was feted by the Ladies Benevolent Society who also provided him with financial support. He spent two years in Ithaca from 1845 to 1846 as the minister of the St. James AME Zion church there. That church is still an active part of the south side community in Ithaca. Listed on the National Register of Historic places, it is documented as a station on the URR. Loguen continued his ministry and abolitionist activity in Troy where he met Enoch Moore, likewise a fugitive slave. He persuaded Moore to move to Little Falls from Troy in 1851.

Headstone of Enoch Moore in the African American section of the Church Street cemetery in Little Falls.

Moore was instrumental in founding both AME Zion churches in Little Falls. The first was built in the early 1870s “and was accomplished thro[ugh] the efforts of Enoch and Cornelia Moore, two of the most popular and highly regarded colored residents of the community,” (Little Falls Evening Times, October 17, 1934). The second church, located on West Main Street near Furnace Street, became a hub of activity for the “colored community” of Little Falls. It was razed in 1934.

Rev. George Bosely served as pastor and he and his family resided with Moore and his family for a time. Clearly, Moore was a political activist, attending state antislavery conventions where he met Rev. Loguen. As such, he was likely a key figure in strategy discussions concerning fugitives and black suffrage at the 1855 “colored community” celebration held at the Little Falls Temperance Hall. During the Civil War, Moore recruited black enlistees in the famed 54th Massachusetts Regiment. Following the Civil War, Moore was a well-known cabinet maker and caterer for both black and white parties and was often quoted in the local papers. One article referred to him as the “illustrious African bard.” He died in 1882 and is buried in what was referred to originally as the “Colored Burial Ground” in the Church Street Cemetery. This area is now designated as the African American (AA) burial ground. A brief obituary of “Colonel” Enoch Moore appeared in the December 1, 1882, edition of the Herkimer County Journal. In the obituary, it is stated that he was, “quite a politician in his way, and always figured prominently in colored State conventions.” Unlike many of the other graves in that area of the cemetery, his stands out being marked with a large headstone indicative of his station in the community.

Little Falls’ strategic location on the Erie Canal was significant because the canal served as a conduit for stations on the URR. Many of these stations were managed by black activists: Stephen Meyers in Albany, Jermain Loguen in Syracuse, Harriet Tubman in Auburn, Frederick Douglass in Rochester, and William Wells Brown in Buffalo. Little Falls, being in the center of this route with access to both the canal and the New York Central Railroad, was a likely stop and given Enoch Moore’s political activity and relationship with Loguen, the AME Zion church was the likely station.

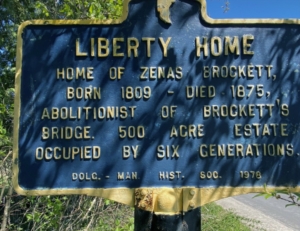

Historical marker on Brockett’s Road approximately two miles outside of Dolgeville, marking the site of Zenas Brockett’s farm (Liberty Home). This marker stands in front of the second house built by Brockett.

In 1857, following the Supreme Court’s infamous Dred Scott decision which held that Congress could not deprive property owners of their slaves and neither slave nor free blacks were considered citizens of the United States and “possessed no rights the white man was bound to respect,” efforts intensified among Rev. Loguen, Moore and all Zion churches along the URR network. More fugitives now sought safety in Canada. As an agent on the railroad, Moore’s job was to provide food and shelter for fugitives and get them safely to the next station and agent. If, for some reason on a given day, the canal or railroad route was not possible, Moore had the option of sending the fugitives approximately three miles north to the farm of another agent, Zenas Brockett.

The Brockett family immigrated from Germany to England to America. Amos Brockett, father of Zenas, moved to New York and his oldest son, Zelphi bought the tavern by the bridge on the East Canada Creek. A little settlement gradually sprung up and became known as Brocketts Bridge (later named Dolgeville in 1881). Its location was likewise significant being on the Military Road which ran from Albany to Sacketts Harbor with easy access from there to Canada.

Zenas Brockett, minister and abolitionist, broke from the Baptist Church when it refused to take a stand on the slavery issue and became a member of the abolitionist Union Church. In 1832, he purchased land two miles west and his farm later became known as Liberty Farm, a station helping many fugitive slaves escape to freedom. Due to the dangerous nature of hiding and helping fugitive slaves, no newspaper accounts exist of this activity. An address given by John Koetteritz to the Herkimer County Historical Society in 1902 stated, “The best known member of the Brockett family was Zenas Brockett, who residing at his beautiful home called Liberty Home, was for many years a leader of the Anti-Slavery Party of Central New York. His place was a station on the underground railroad and many a slave was here protected and sheltered on his way to Canada.” In addition, letters from family member F. M. Tuttle, a great, great nephew of Zenas, and stories from family friends like Minnie Helmer and Hannah Ransom, which follow, help paint a picture of Brockett’s activity as an agent at Liberty Farm, later Liberty Home. (This information and the following accounts are found in the booklet written by Eleanor Franz, The Underground Railroad in Brocketts Bridge, copyright 2000.)

The first house at Liberty Farm, having been built on a slope, had a cellar and kitchen at the basement level, and the inner cellar was accessed from the kitchen. Slaves were fed and sheltered in the inner cellar, their food carried in from the kitchen. The Ransom family had a hired man who also worked for the Brocketts. He recalled often being asked to harness a team of horses in the late afternoon or early evening. The following morning, the horses would be in the barn tired and sweaty as though they had traveled a long distance. He was instructed to let them rest all day. At times, he recalled hearing voices at night along with the sound of horses and wagons coming and going, but never saw any slaves.

The most likely route taken was over Minor Road behind the house, across Peck’s Ridge (Peckville Rd.), then right to the Old State Road at Chimieleski’s farm, then north. Chimieleski’s farm was also rumored to be a safe house. Alternatively, the fugitives may have been moved to the Erie Canal only six miles away for portage to Lake Ontario.

According to a grandson of Zenas, one of many Brocketts named Charles, on Sundays when the Brocketts were at church, the fugitives would venture out and roam the house a bit. One Sunday, some curious neighbors entered the house to have a look. They were surprised and sent packing by Zenas Brockett who returned from services early. According to family and friends, Harriet Tubman was a frequent visitor to Liberty Farm as were Gerrit Smith, who attended his funeral, John Brown, Rev. Jermain Loguen, and Frederick Douglass. In addition to his conductor duties, Zenas Brockett was a member of the Anti-Slavery Party and donated money to the abolitionist cause and those who supported it.

Part of the mural depicting the Underground Railroad station at Zenas Brockett’s farm (Liberty Home) just outside Brockett’s Bridge (later Dolgeville) done by James Newell in 1940.

This author was able to speak with the current resident of Liberty Home, Charles T. (for Terrific as he laughingly joked) Brockett, the fifth generation of Brocketts to occupy the land. He confirmed the current residence is the second house Zenas built on the property, down the road about a half mile from the original home. Rumor has it that this second house also sheltered slaves in one of two back halls. Also, Charles T. dispelled the tale that the slaves were sheltered in a cave near the first house. The subterranean nature of the sunken kitchen and cellar most likely led to that tale. Other than that, he had no family stories to tell, but did recommend the work of Eleanor Franz and was happy to know I’d used her work as a major source of information. We also spoke of the mural done by artist James Newell that adorns the walls of the Dolgeville Post Office. Newell was a WPA (Works Progress Administration) artist best known for his fresco murals. The mural entitled “The Underground Railroad” in the Dolgeville Post Office was commissioned by the Section of Fine Arts of the Federal Works agency in 1940.

Brockett’s obituary was quite lengthy, published in the Little Falls Journal and Courier, June 5, 1883. Among other words of praise, this was written, “His neighbors loved him and the downtrodden of every race lost in him a friend whose sincerity was never doubted and whose charities were only measured by his ability.” His funeral was held at the Union Church in Salisbury, presided over by three clergymen. Following the funeral, “an immense concourse of friends and neighbors,” notables like Gerrit Smith, and a delegation of “colored men who have in him lost a true and earnest friend” followed his remains from the Union Church to the grave site in the cemetery near there. The obituary includes a letter from his friend A.S. Faville, another Dolgeville abolitionist, who praises Brockett with these words: “What a solace to you to survey the results of fidelity to your life work. The poor slave is free, the temperance reform has made great progress, education has thrown off the vail of bigotry and sectarianism, the world is brighter and better than when you came into it.”

Enoch Moore and Zenas Brockett’s lives shared many similarities. Both performed the same function on the URR, both worked with many of the same noted abolitionists, both took great risks, both were by all accounts respected individuals. However, following their deaths, their differences become more apparent. Brockett was celebrated by a large contingent of notable individuals. Information about his life and work was relatively easy to obtain. Moore’s obituary is brief in comparison to Brockett’s and lacking in detail. Information about his life was not easy to find. Since Moore was a well-known citizen of Little Falls, performing catering and cabinet making for blacks and whites alike, a minister responsible for both AME Zion churches in Little Falls, often quoted in the local papers, it can be assumed his funeral was well attended, but his obituary contains no mention of this and thus it remains conjecture.

The world may have looked “brighter and better” to Faville in the late 1800s, but darkness still lurked, and more struggles lay ahead. Both Moore and Brockett, along with all the others involved in the URR, were dedicated to the rights of freedom and equality regardless of personal danger. The battles for those rights continued beyond the Civil War. The Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery “within the United States or anyplace subject to their jurisdiction.” Then, Jim Crow laws in the South threatened that new freedom and continued to do so into the mid-twentieth century. The Civil Rights Movement fought for years, its members shedding blood, and enduring physical punishment, even imprisonment, seeking freedom from Jim Crow. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965 were milestones in the struggle to end discrimination and extend civil, political, and legal rights to African Americans. However, recent political events have shown us that rights once guaranteed can be taken away. Forces exist who are determined to focus on division rather than unity and threaten to turn back history even further. Though the world may be “brighter and better” than in Moore and Brockett’s time, it’s still a long, slow, difficult train ride on the road to freedom and equality for ALL.

Cynthia Holick Foley is a member of the Little Falls Historical Society.