Robert Brown Elliott

Robert Brown Elliott, 1874

Robert Elliott was born on August 11, 1842, likely to West Indian parents in Liverpool, England. He received a public school education in England and learned a typesetter’s trade. Elliott served in the British Navy, arriving on a warship in Boston around 1867. Historical records show that in late 1867 Robert Elliott lived in Charleston, South Carolina, where he was an associate editor for the South Carolina Leader, a freedmen’s newspaper owned by future Representative Richard H. Cain. Elliott married Grace Lee, a free individual from Boston or Charleston, sometime before 1870. The couple had no children.

In October 1870, Republicans in a west–central South Carolina congressional district nominated Robert Elliott over incumbent Solomon L. Hoge to run for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives. The district included the capital, Columbia, and had only a slight black majority. The seat was once held by Representative Preston Brooks, notorious for his caning assault on Senator Charles Sumner in 1856. Elliott faced Union Reform Party candidate John E. Bacon, the son of a prominent, aristocratic, low country family. The election was contentious. Bacon accused Elliott of using his position on the committee on railroads in the state legislature to line his own pockets. Though the New York Times predicted Bacon’s victory, Elliott soundly defeated him with 60 percent of the vote. He was sworn in to the 42nd Congress (1871–1873) on March 4, 1871.

White colleagues received Elliott coolly. His dark skin came as a shock, as the two other African Americans on the floor, Joseph Rainey and Jefferson Long, were mixed-raced. Described as the first “genuine African” in Congress, Elliott seemed to embody the new political opportunities—and southern white apprehensions—ushered in by emancipation. Of the day he delivered his first speech, Elliott recalled: “I shall never forget. . . I found myself the center of attraction. Everything was still.” Furthermore, his politics were more radical than his African–American colleagues’, and his unwavering stance for black civil rights made many Representatives of both parties wary of his intentions. Elliott was given a position on the Committee on Education and Labor, where he served during both of his terms.

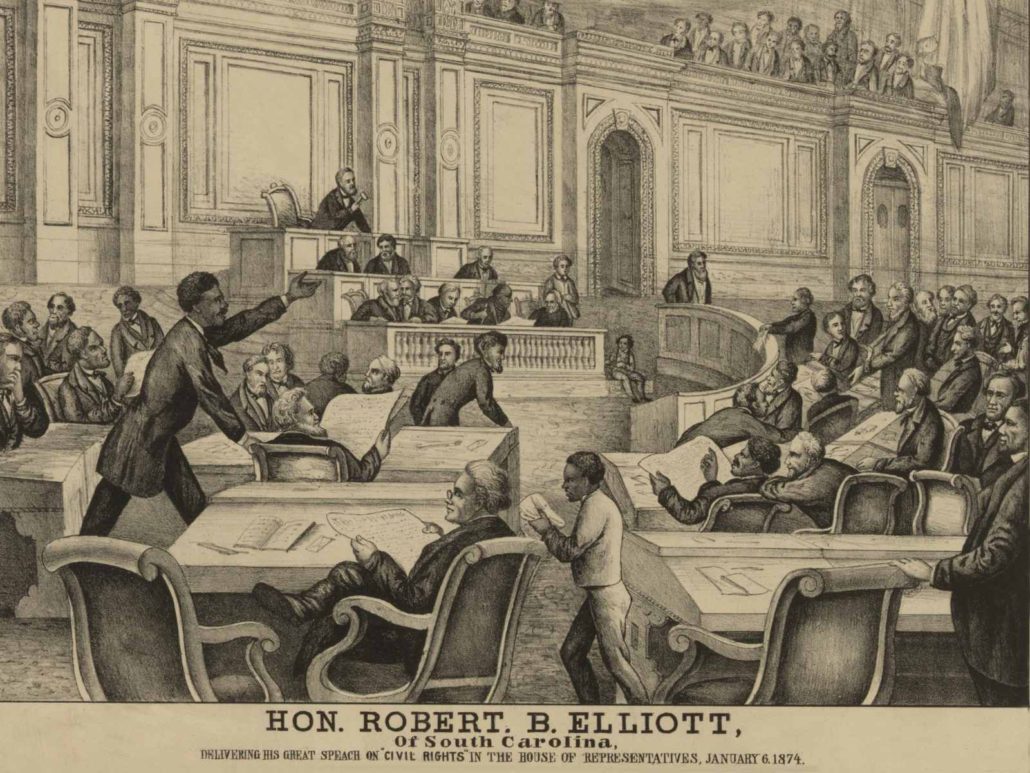

During his second term, Elliott worked to help pass Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner’s Civil Rights Bill, to eliminate discrimination from public transportation, public accommodations, and schools.

Elliott gained national attention for a speech rebuffing opponents of the bill, who argued that federal enforcement of civil rights was unconstitutional. Responding to former Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephens of Georgia, who had been re–elected to the House, Elliott reaffirmed his belief in the right and duty of Congress to legislate against discrimination. He concluded by evoking the sacrifices made during the Civil War and asserting that its true purpose was to obtain civil rights for all Americans, including women, who experienced discrimination. Elliott undoubtedly drew upon a large reserve of personal experience with racism. Like other African–American Representatives, he faced discrimination almost daily, particularly in restaurants and on public transportation. Before a packed House, Elliott stated his universal support for civil rights,

“I regret, sir, that the dark hue of my skin may lend a color to the imputation that I am controlled by motives personal to myself in my advocacy of this great measure of national justice. Sir, the motive that impels me is restricted to no such narrow boundary, but is as broad as your Constitution. I advocate it, sir, because it is right.”

Elliott’s youthful appearance and the “harmony of his delivery” contrasted sharply with those of the elderly Stephens, who, confined to a wheelchair, dryly read a prepared speech. The Chicago Tribune published a glowing review, noting that “fair–skinned men in Congress … might learn something from this black man.”

“Civil Rights: Then and Now”

National Conversation on #RightsAndJustice in Atlanta

As part of its Amending America initiative, the National Archives and Records Administration presented a National Conversation on Civil Rights and Individual Freedom in partnership with the Jimmy Carter Presidential Library and Museum in Atlanta, Georgia, on May 20-21, 2016.

“This two-day event addressed the challenges to and future of civil rights and individual freedom, and featured a Q&A session with former President Jimmy Carter and Derreck Kayongo, CEO of the National Civil and Human Rights Center.. Their discussion was followed by a panel on “Civil Rights: Then and Now,” moderated by Jelani Cobb. Panelists include Ouleye Ndoye Warnock, Columbia University; Karin Ryan, Senior Policy Advisor on Human Rights and Special Representative on Women and Girls for the Carter Center; Lisa Williams, founder, Circle of Friends; and Dr. Kurt Young, Clark Atlanta University.” – Amending America

“Where are we on our journey for human rights? Because civil rights, as we understand it, is very specific to participation–access to participation in civic life.”

– Karin Ryan“The definition of ‘human’ is actually the real root of the problem when you’re talking about human rights. Whose rights are we protecting?”

– Ouleye Ndoye Warnock

View highlights from the 2016 National Conversation on Rights and Justice in Atlanta.

The event in its entirety can be viewed here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UDOMzqsaen0.

Through our series of National Conversations on #RightsAndJustice, we invite Americans to explore a range of contemporary issues, addressing the tension between individual rights and collective responsibilities, a process that began with the Bill of Rights. – Amending America